Orchid conservation program

The dazzling array of floral forms and seemingly fragile and ephemeral nature of orchids have captured people’s hearts for centuries. But they’re not only beautiful and mysterious - orchids are also one of the largest plant families globally, with complex life histories that also lead them to being the most threatened group of flora.

Kings Park Science seeks to understand the biological complexities of orchid interactions to deliver conservation solutions not only for the orchids themselves, but for their environment, pollinators and fungal partners.

Did you know?

Orchids are one of the largest flowering plant families on Earth with more than 30,000 known species.

Orchids have the smallest seeds of any flowering plant, and it is estimated that less than one seed per capsule (34,000 seeds) will survive to adulthood.

Western Australia is rich in orchids and is home to 470 species, with one third of these holding a conservation listing. Sadly, 10% of these are listed as a Threatened Species.

95% of Western Australia’s orchids are found nowhere else in the world.

The process of pollination – orchids in disguise

Like most flowering plants, orchids require help to move pollen from one plant to another and set seed. Orchids employ some of the most intricate flower mechanisms to enact pollination, often so specifically that they only engage one pollinating species.

Using scents ranging from smelly socks to sweet nectar, pheromones as chemical lures, colourful flower impersonations and mechanical trapping of pollinators, orchids know all the tricks. Understanding how pollination occurs, and understanding the role of the insects involved, helps scientists understand when a site may no longer be supporting seed set or pollinator presence, and provide information on how to restore pollination services.

Perfect Pairs: teaming up with fungi to survive

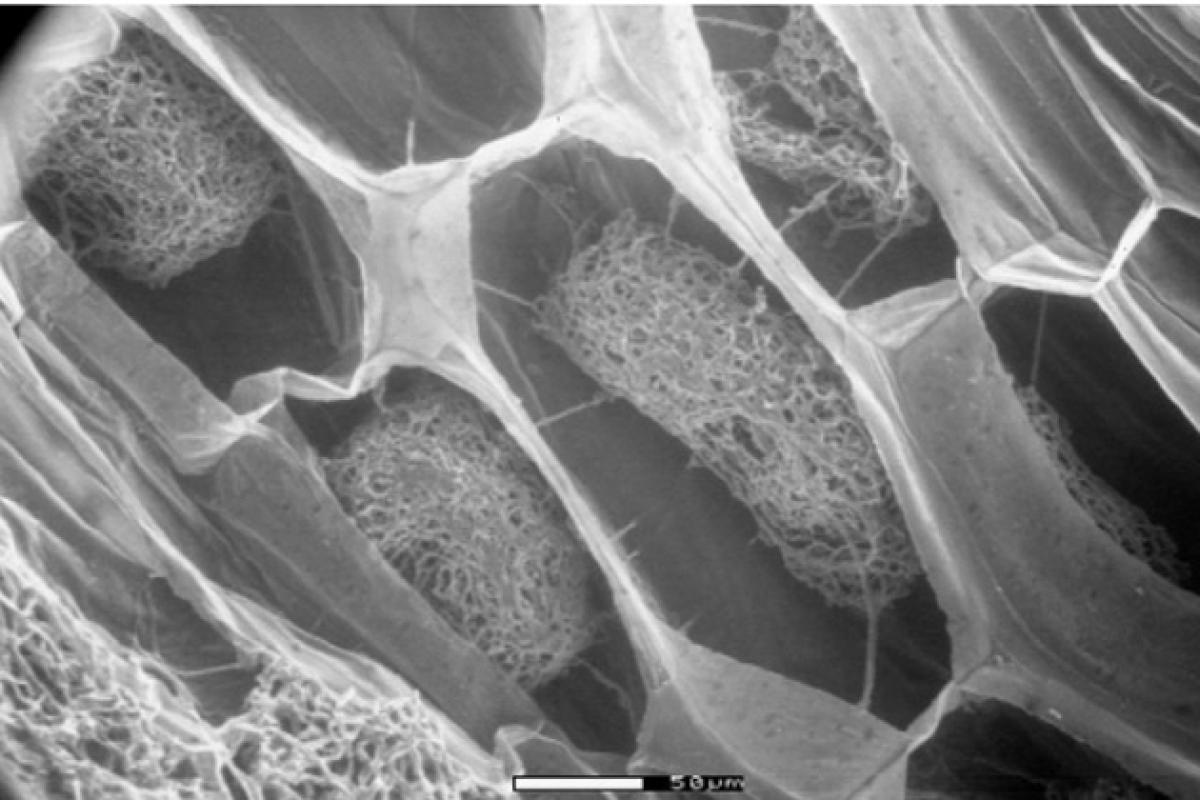

Orchids have almost no root systems and are quite poor at obtaining soil nutrients independently, so they team up with specific fungal partners to become extremely effective at foraging for soil nutrients. This is a two way relationship, as once orchids are established they can give back to their fungi by providing a solar powered feed of carbon that the fungi could never access on their own. This symbiotic relationship is vital for orchid germination to occur and is re-established between plant and fungi annually.

Understanding and being able to harness this orchid-fungus partnership for each orchid species is key to plant propagation and ex situ conservation (in glasshouses, cryostorage and garden displays) and habitat management in the wild.

Translocation research

Translocation is a conservation option that can be used to bring critically endangered species back from the brink of extinction. Orchids have many ecological interactions that make them a particularly challenging group to translocate. Bringing together research in the pollinator and orchid-fungal space, translocation research conducted at Kings Park seeks to deliver science-informed conservation outcomes for our most threatened species. Translocations with the goal of a self-sustaining population places an emphasis on site selection based on pollinator presence.